On October 24, 1791, a man named Douwe Posthuma passed out drunk in a tavern in Amsterdam. His behavior, obviously, wasn’t welcomed back home, and the brawl between father and son ended up in the records of street conflicts. A relatively unremarkable family feud seemed to have been forgotten in history until it emerged more than two centuries later in a digital reconstruction of the city’s street life, a project of the University of Amsterdam. The common narrative around Big Tech and AI paints them as tools of tomorrow, technologies that are shaping a smarter future. But in practice, they’re also digging deep into the past. History, culture, and cultural heritage are being subjected to algorithms, codes, and large language models. It is not only about preservation, it’s about transformation: of what history is, who gets to tell it, and how we explore it. No matter how big or small, every voice of the past can now be heard.

From one city to a continent

What Douwe Posthuma didn’t know was that he would be virtually awakened at the crossroads of digital technology and cultural heritage. The project where his and thousands other names appeared – “Gender and Urban Space in Amsterdam 1600-1800” – is one of the many initiatives related to the approach of the large European Time Machine project. Bringing together researchers, archives, museums, tech developers, and private sector partners under the “Big data of the past” motto, the Time Machine Organisation aims to digitally reconstruct the past across hundreds of cities and regions.

Supported by the European Commission and some EU member states, it is now a network of 600 institutions across 33 countries, with projects currently active in 86 locations. The goal is both ambitious and user-friendly: drafting the digital version of history – one we can search like we search the web today.

The work of these projects, united under the alliance of the Time Machine Organisation, ranges from scanning documents to 3D scanning existing or partly remaining buildings using photogrammetry or lasers, followed by the reconstruction of destroyed parts. It also requires localizing images, postcards, paintings, linking place and person names, and so on.

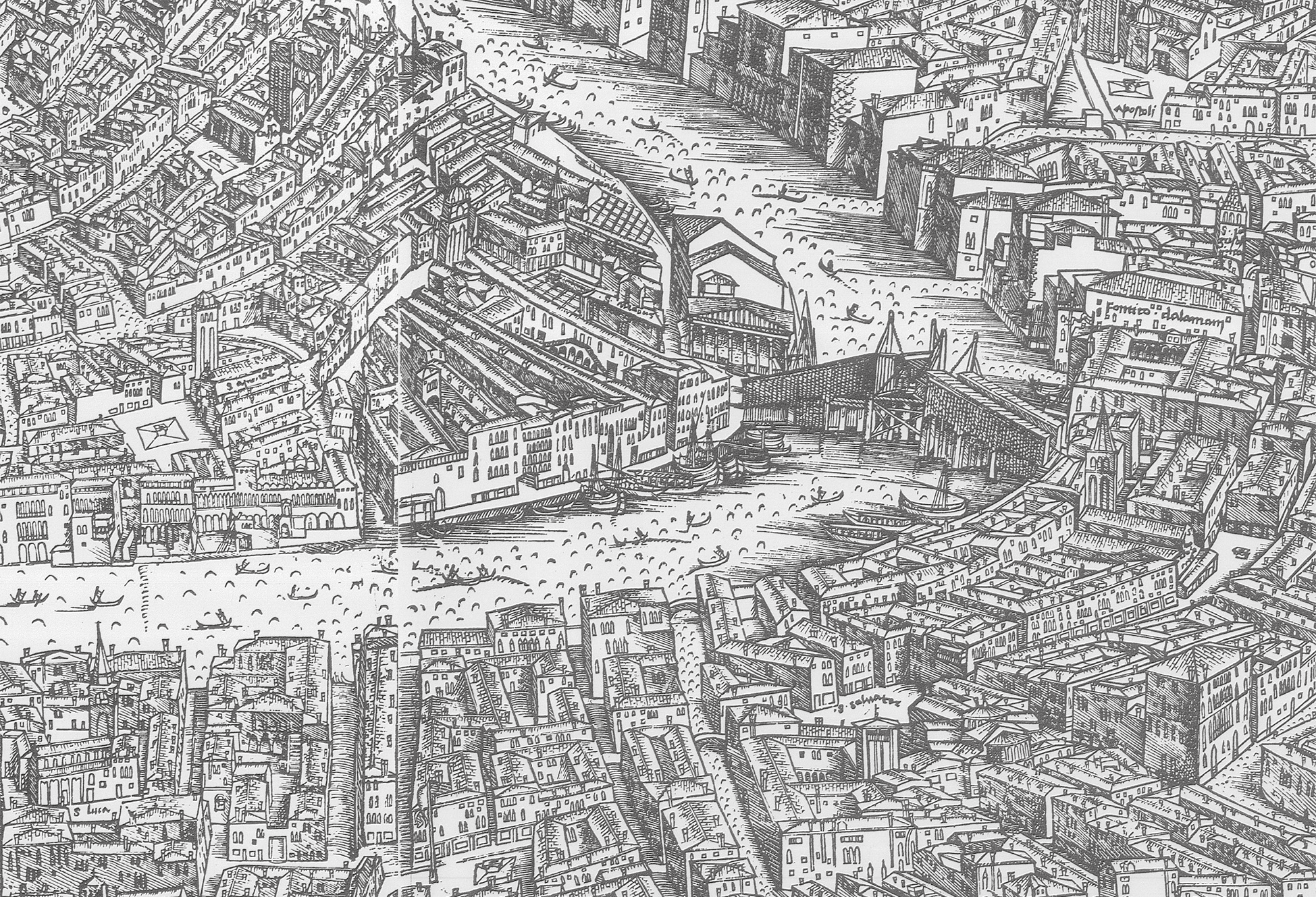

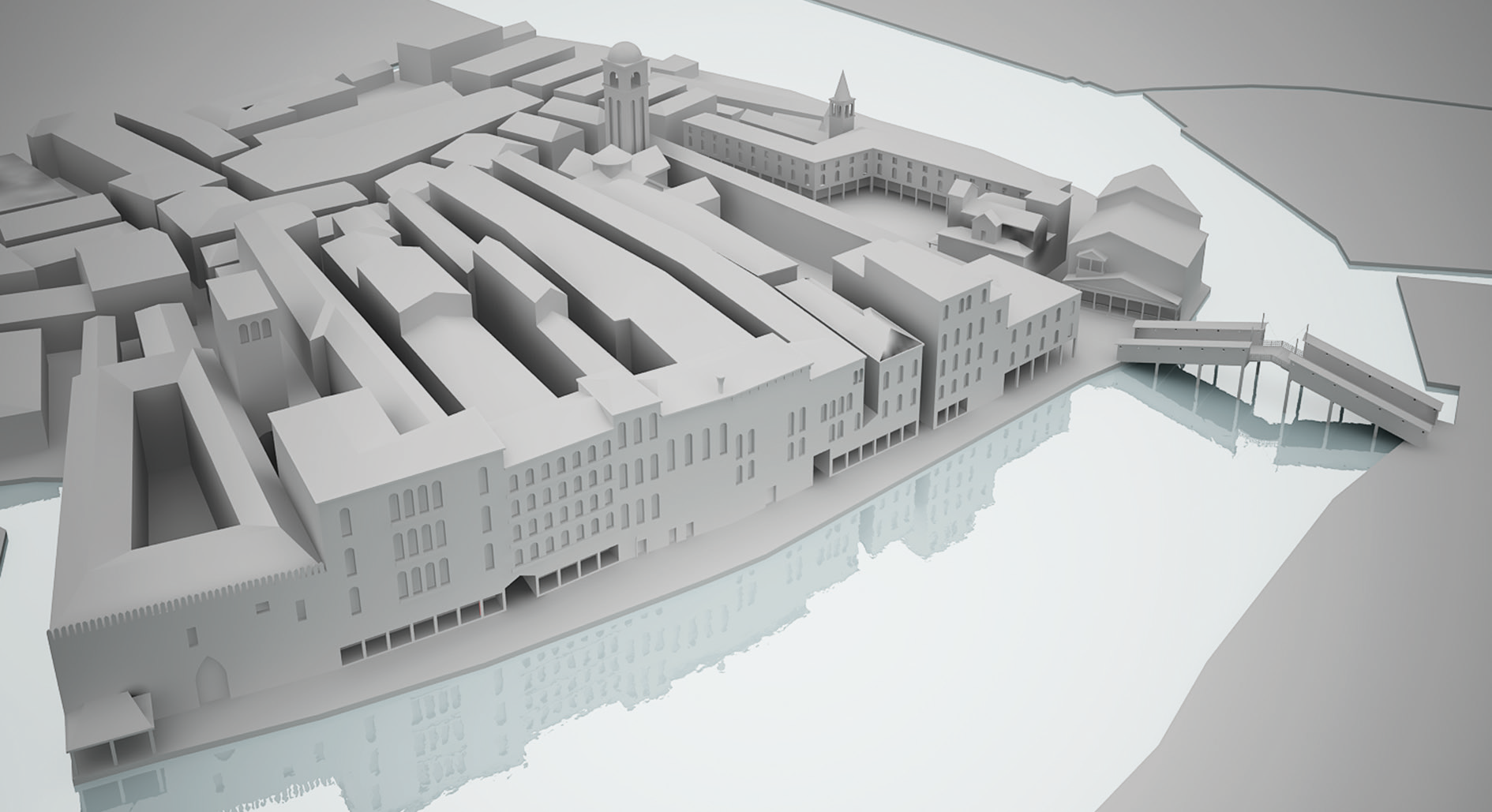

An ideal example of how accessible the history of Europe might look is a multidimensional digital model of Venice, reconstructing a thousand years of its history into an animated map – the project that sparked the initial Time Machine concept.

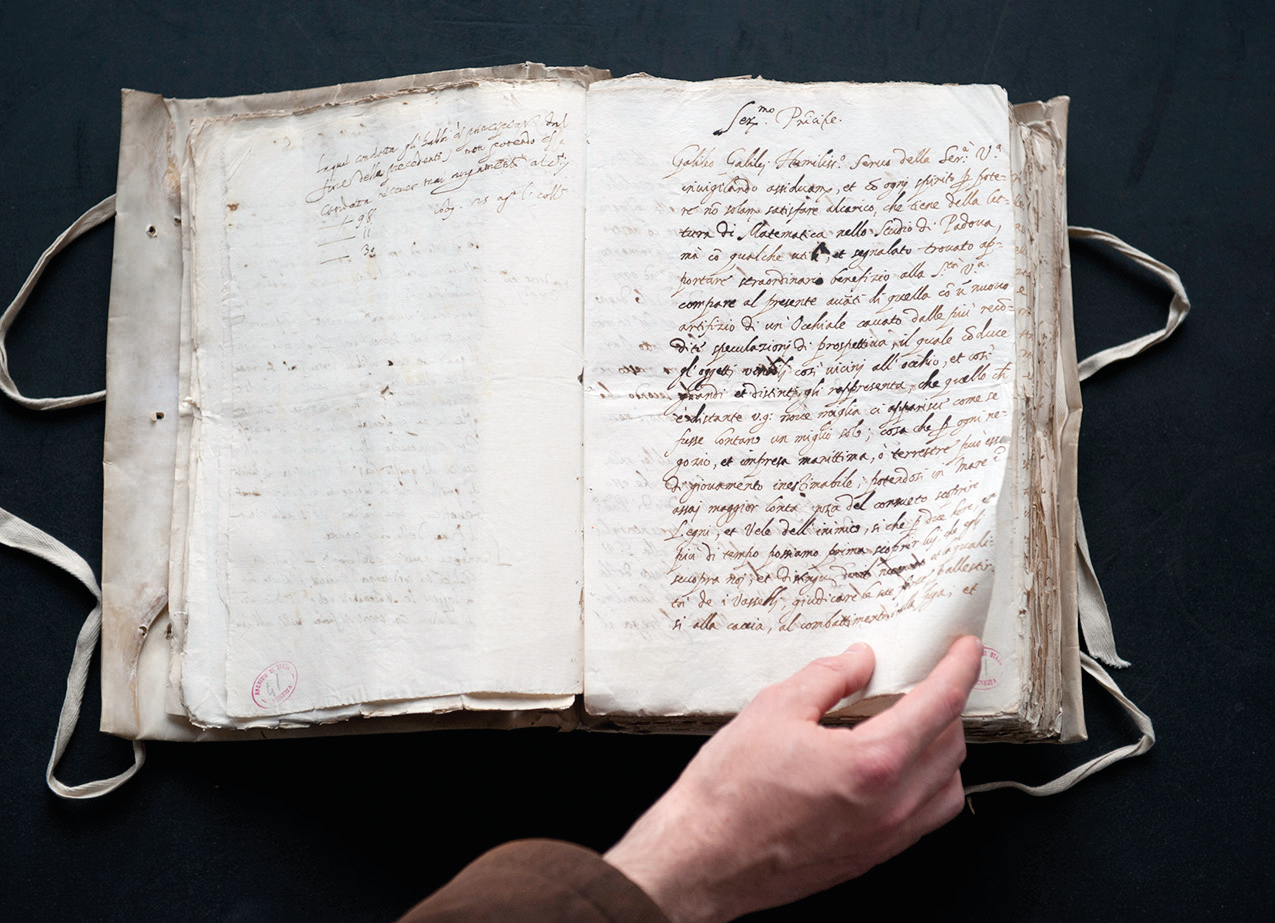

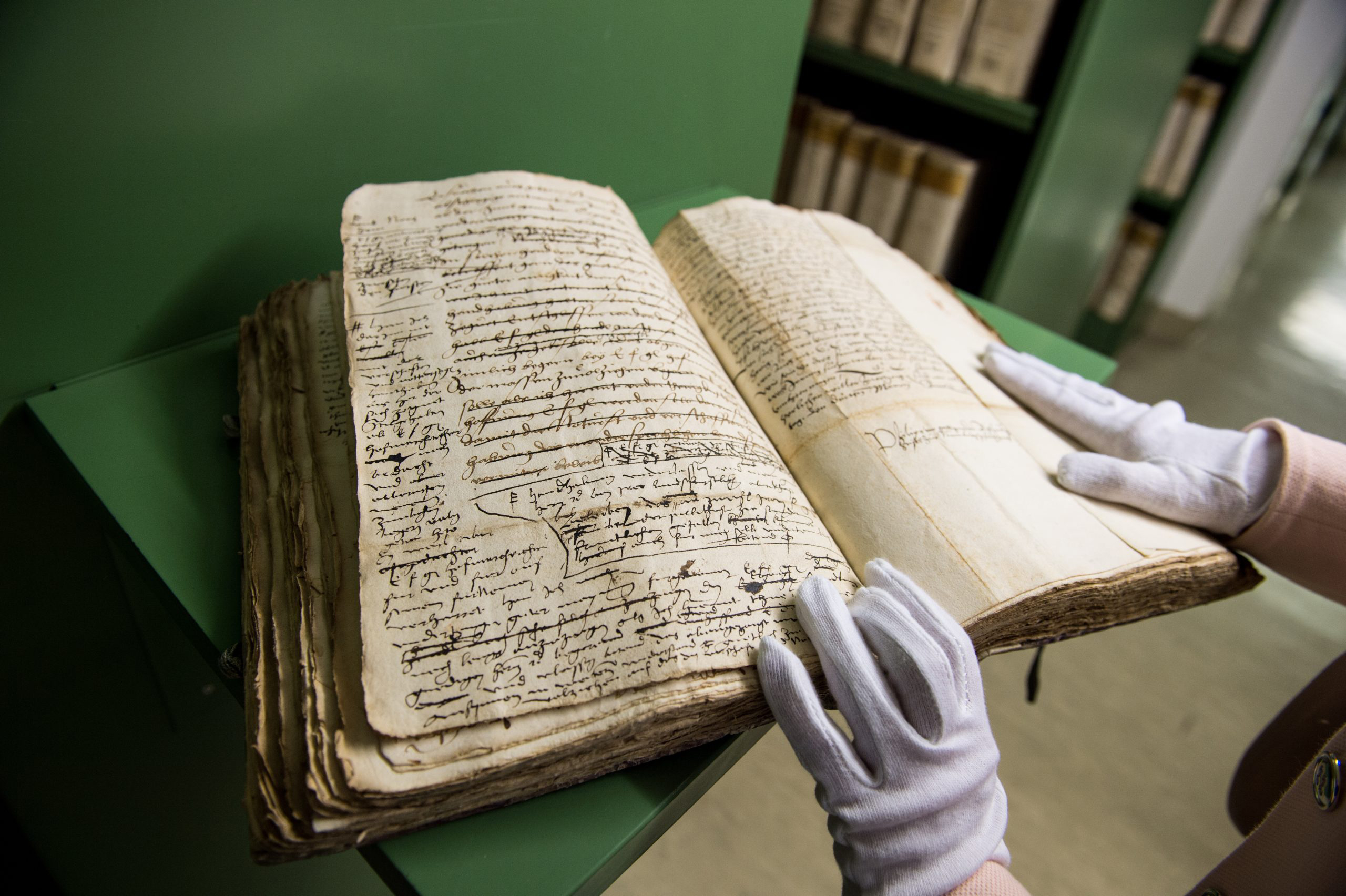

In just six years, from 2012 to 2018, researchers from the École Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne and the University of Venice Ca’ Foscari, went through the census records, tax papers, and maps stored in over 80 km of shelving in the State Archives of Venice, the Giorgio Cini Foundation, and other heritage institutions. Opening centuries-old archives, page by page, was only possible through a combination of high-resolution scanners and robotic systems.

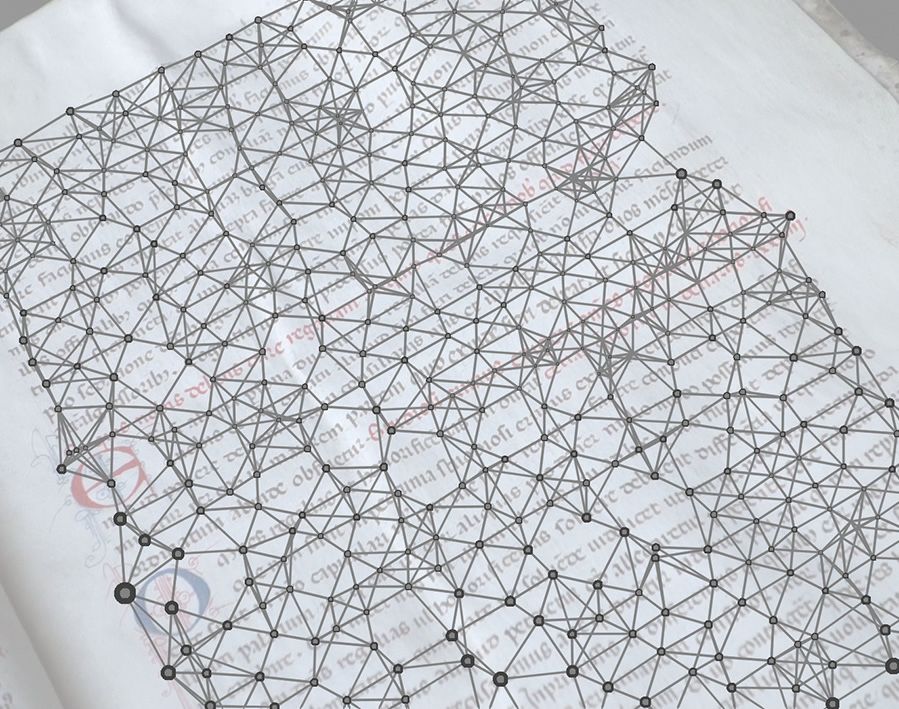

Unveil the past with the technologies of the future

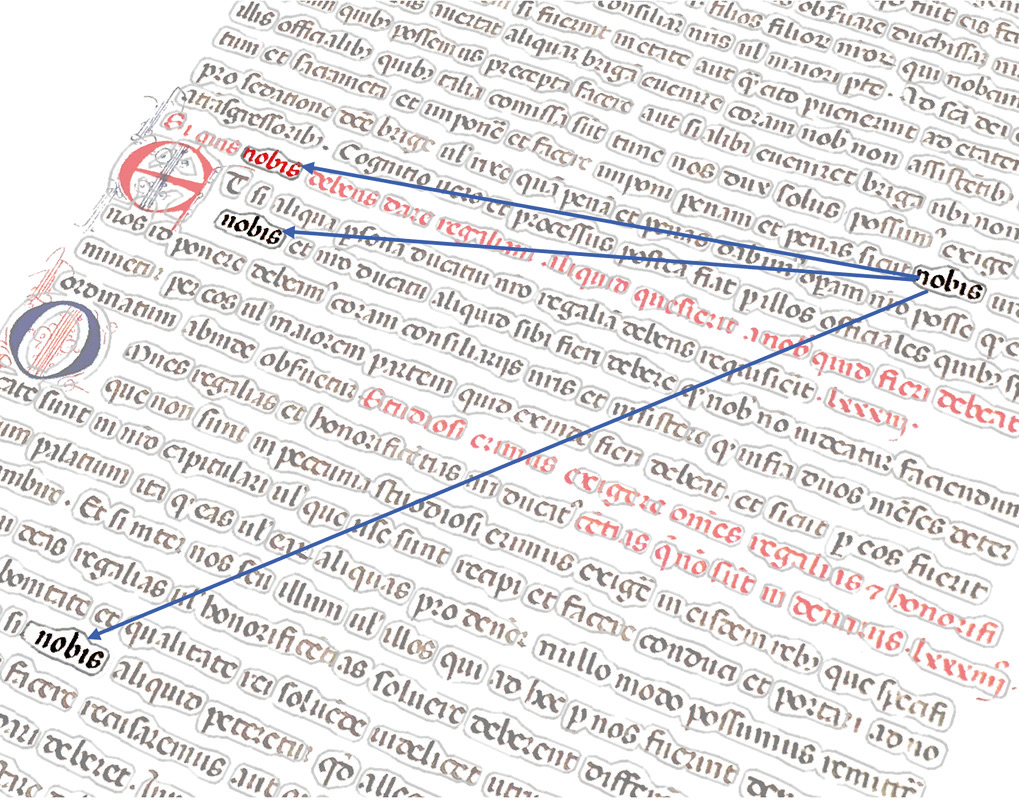

Experimental work also explored the use of X-ray tomography, enabling the digitization of manuscripts without physically opening them. In the second phase of the project, which started in 2019 with the support of the Swiss National Science Foundation, handwritten text recognition, automatic map segmentation, and other artificial intelligence technologies made the documents indexed and searchable in time and space, sharpening the optics of historians into the past. These efforts toward automation went hand in hand with patient manual curation to refine and tune the processing pipelines. Venice is now perhaps the place in the world with the highest level of digital historical information density, thanks to these 12 years of research efforts.

“All of this can be directly accessed and explored through the Time Machine Atlas, shares Frédéric Kaplan, president of the TMO, director of the College of Humanities at EPFL. “Anyone can zoom in on a street or canal, select a specific historical period, and access the available historical information digitized during the project – including administrative records, maps, photographs, and 2D or 3D reconstructions produced by scholars. This opens the way for a kind of history, not only focused on famous individuals or monumental sites, but on the lives of ordinary people”, he says.

Ethics for the past and rules for the future

The idea of recovering the texture of everyday lives drives many of the archival initiatives emerging across Europe. The breakthrough is not how deep we can look in history with cutting-edge digital tools, but through whose eyes we can look. Technologies attune to diversity even when the past clearly did not. Even historical indexing becomes a political act, such as in the digital resurrection of colonial records. One such effort – another project of the University of Amsterdam – digitised colonial-era wills of people hired by the Dutch East India Company. Its 17th-20th century archive was indexed and searchable only by the names of male testators. Only a recent analysis revealed that nearly 60 percent of these wills mention at least one woman, and about 30 percent mention a non-European person. Now, with digital methods, all these thousands of previously unsearchable names are available in the database to historians.

Ethical concerns of the AI era are different but no easier. As open cultural data wins new sectors – from tourism and education to creative industries and training of large language models, concerns arise around the way it’s being exploited. “Openness means something different today than 10 years ago: it’s not only about intellectual property and copyright, but it’s also about respect and privacy. These are one of the biggest challenges for Europe when it comes to sharing data, access to data”, says Maria Drabczyk, member of the International Advisory Committee of UNESCO’s Memory of the World Programme, board chair at Centrum Cyfrowe (Poland).

From digital past to the shared future

In Europe, digital cultural heritage is seen as a shared past. Since 2008, these efforts have been led by Europeana, an initiative established by the European Commission. What started as a kind of European digital library with 4.5 million digital objects in its archive is now a movement, a standard-setting body, and digital infrastructure providing access to over 62 million digital objects – from scanned manuscripts to audio recordings, artworks, and photographs from more than 4000 European cultural institutions.

“Europeana started to, what we call, democratise access to cultural heritage data. We feel not only it should be as open as possible, but findable, accessible, transparent, and reusable”, says Harry Verwayen, General Director of the Europeana Foundation. The prioritization of a “to be digitized” sites or objects is up to national governments and cultural institutions. When Europeana launched a campaign among all EU members to submit at least one high-quality 3D digital asset, challenging governments to really narrow national historic artefacts. By the end of 2024 there were 37 submissions, among them sites that only exist digitally: the Great Synagogue of Erfurt (Germany) destroyed in 1938, or the full reconstruction of Roman Triumphal Monument – Heidentor (Austria), of which only one arch actually remains – as a reminder of richness and fragility of Europe’s cultural landscapes, but also history.

“The EU ambition is to have digitized in 3D all monuments and sites at risk by 2030, and half of the most visited monuments, because they are at risk the most,” explains Mr. Verwayen. But the task is far from complete. “For many countries, 3D digitization proves to be a very complicated and costly affair, and Europeana is supporting them throughout this process”.

The past on your terms

The idea of interacting with the past, not just learning about it, doesn’t sound as futuristic as it once was. “I think a historical dimension will be part of most new endeavours when interacting with virtual or augmented worlds”, says Harry. A historian himself, he hopes to preserve the memory first to make it evolve.

“Archives represent facts, and it’s important that everyone has access to the facts before they start piecing history together into a story that makes sense. The bigger goal is to contribute to a better world that is, at the moment, very polarized. If you have access to this incredibly vast pool of historical resources, you’ll be able to find completely new narratives in there,” Harry emphasizes.

With the unprecedented wealth of historical data now made available, we have access to vast archives of human experience like never before. Yet even as technologies unlock these records, it remains the work of historians and scholars to interpret, question, and weave them into the stories that shape our understanding of the past. As Mr.Verwayen puts it, “a hybrid intelligence.” “It is human intelligence with the support of AI intelligence. That could be a very powerful combination”. Because in the end, in the digital future, every one of us will have our role in making and shaping history.