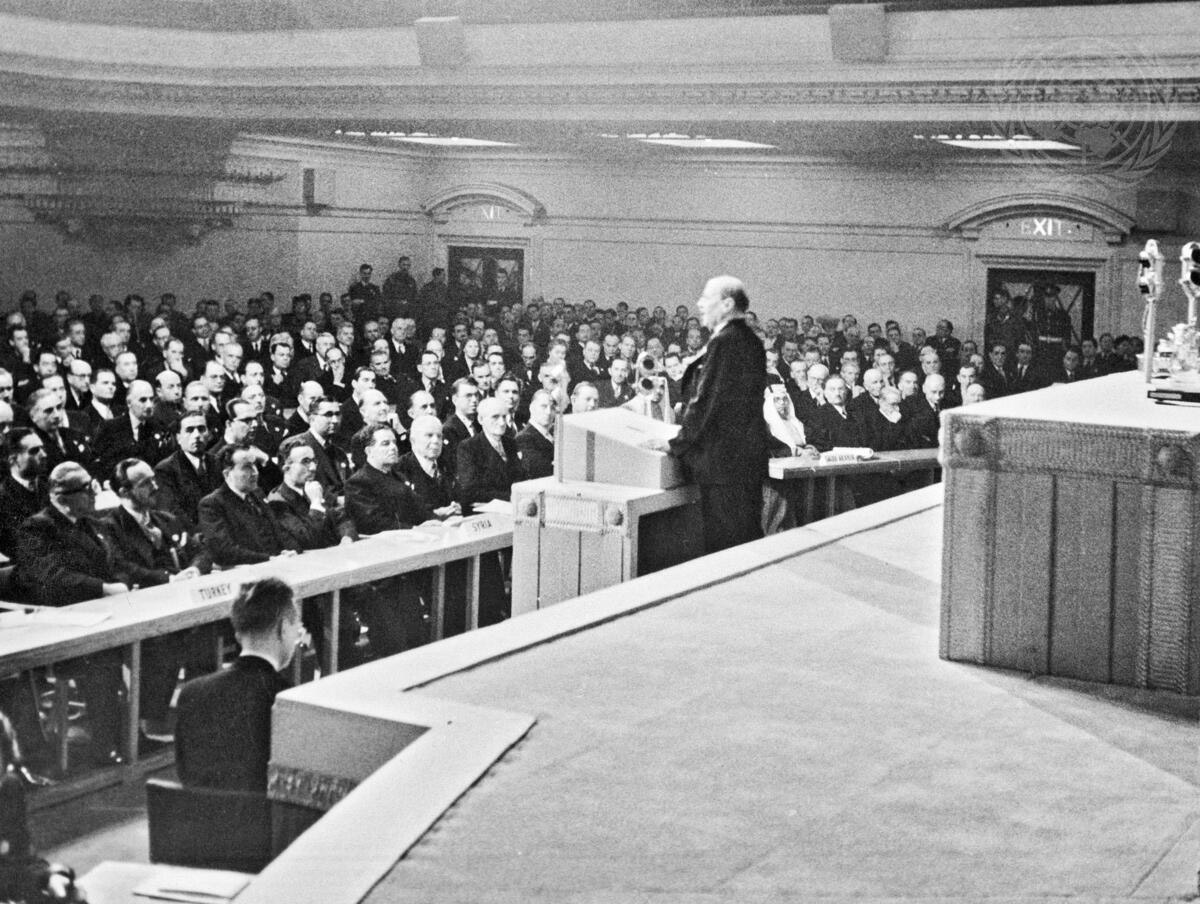

Can the United Nations reinvent itself at 80?

Inside U.N. chief António Guterres’ bold gamble to streamline mandates, tame finances, and keep diplomacy alive.

Reform has already begun to feel passé as the months of this year have rolled by. Projecting into the future makes policy and peace processes harder to chart, especially in an era of division and polarization.

This year, the Secretary-General has faced one of the most challenging landscapes in recent memory. The last to bear such weight was Kofi Annan, whose tenure was marked by Rwanda and Srebrenica, the Iraq War, and Sudan. He endured controversy and the “please all, please none” paradox that comes with leadership. Annan managed this balancing act, inspiring those around him and earning, alongside the U.N., the Nobel Peace Prize for revitalizing the institution.

Today, that challenge falls to António Guterres. He leads at a time when polarization has paralyzed communication, when diplomacy resembles a checkerboard more than a straight path, and when technology accelerates faster than our ability to process or adjust. Yet his message is clear: diplomacy must remain a level playing field, even in times of escalation.

The road to UN80

The UN80 Initiative is his attempt to reform and adapt in an age of disruption. Introduced at a moment when people, shaken by COVID, economic fragility, and overlapping crises, feel more vulnerable than ever, it seeks to bring clarity to a system weighed down by accumulated obligations. And though finance may seem uninteresting, it is as vital and volatile as any crisis: a tide that can either overwhelm or be tamed.

Launched in March, the first informal meeting of the initiative was held on May 12. Its purpose was to introduce the urgency of restructuring and aligning processes within the U.N. for better use of limited resources. This marked the initiative’s entry into Assembly discourse.

On Aug. 1, Guterres presented the Report on the Review of Mandate Implementation, the centerpiece of UN80. He outlined three reform workstreams: Efficiencies & Improvements, Mandate Implementation Review, and Structural Changes & Program Realignment. His message was blunt: “The path forward is yours to decide.” The Secretariat’s role, he said, is to provide capacities and inputs, but the choice rests with member states.

By placing the issues squarely before them, he acknowledged both the scale of the problem and the need for collective resolve. UN80 aims to relieve the fatigue of information overload, which too often clouds judgment and leads to fragmented decision-making.

Redefining the U.N.’s mission

The initiative seeks not only to preserve the U.N.’s three pillars of peace and security, human rights, and sustainable development, but also to restructure its financial foundations. The signs are visible: buildings closed, costs pared, departments slimmed down, staff redeployed. Through time, the scale of change will be more evident.

Alongside UN80 sit other reforms. The Pact for the Future, led by Germany and Namibia in 2024, was designed to reassure a drifting public by building trust and giving the young a voice at the table. U.N. 2.0, a modernization drive, seeks to prepare the U.N. for governing technology and uncertainty. Taken together, these initiatives reflect a determination to preserve the U.N.’s founding purpose while adapting its machinery to withstand financial strain and accelerating global change.

Cutting costs in six languages

For decades, resolutions have accumulated, now numbering more than 40,000, creating an archive so vast that navigating it risks overload and duplication. The Aug. 1 mandate review aims to bring order by streamlining and prioritizing. It is, in essence, housekeeping: retaining what speaks to the present while setting aside the obsolete.

Documents must appear in the six official languages of the U.N. — Arabic, Chinese, English, French, Russian, and Spanish. Guterres said savings could be found in redundant translation and interpretation. Technology is expected to play a decisive role in reducing costs.

A flat budget and rising pressure

Beneath these discussions lies financial reality.

“For nearly twenty-five years, the U.N. has been asked to do more with less.”

The U.N.’s regular budget for 2025 is about $3.7 billion, while peacekeeping costs are about $5.6 billion. The United States pays 22% of the regular budget and 27% of peacekeeping, China about 15% and 18%, Japan 8%, and Germany 6%.

The budget has remained largely flat since around 2000, with inflation steadily eroding its value. Liquidity crises recur, sharpened by arrears from certain member states. These arrears are more than a financial nuisance; they send political signals and create domino effects that undermine trust.

In June 2025, the U.N. cut its global humanitarian appeal by one-third, to $29 billion, its lowest in years, citing donor fatigue. The Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights reported a $60 million shortfall, forcing reductions in field operations.

The Trump administration has proposed eliminating U.S. funding for U.N. peacekeeping starting in 2026, citing failures in missions in Mali, Lebanon, and Congo. It also froze $4.9 billion in foreign aid, including about $800 million for peacekeeping, a decision now tied up in litigation. On Sept. 9, 2025, the U.S. Supreme Court allowed $4 billion in aid to remain frozen while it considers an appeal.

Donor politics and global rivalries

Guterres argued that overlapping mandates have fueled inefficiency and waste. He proposed merging departments and shifting resources into the field to make the system more agile.

Russia and China have resisted U.S.-backed human rights and sanctions mandates, favoring a multipolar order aligned with developing nations. The European Union, while supportive of reforms, is struggling to finalize a €2 trillion, seven-year budget starting in 2028. Analysts warn that rising defense spending could reduce funds available for humanitarian aid and development programs often routed through U.N. agencies.

Diplomats from the Global South have also expressed concern that reforms risk privileging donor priorities over equitable representation.

Merging missions, risking voices

The most visible features of UN80 lie in proposals for structural realignment. Ideas such as merging WHO with UNAIDS, U.N. Women with UNFPA, or consolidating OCHA, UNHCR, and IOM into a single humanitarian body have stirred debate. For some, these proposals represent efficiency and coherence; for others, the risk of losing carefully built expertise and distinctive voices.

Still, the U.N. is not a victim of its circumstances. Like every institution in transition, it adapts, shaping itself to meet realities that have changed since many of its organs and programs were conceived. Resistance to change is natural; so too is debate over what must be preserved. But reform is not about dismantling, it is about clarifying purpose and strengthening function.

Cosmetic shift or real reform?

Every secretary-general in recent decades has attempted restructuring. Guterres’ gamble is that this effort will not be derailed by today’s sharper geopolitical rivalries. Some diplomats warn the current proposals are more cosmetic than transformational and argue that without predictable, sustained donor commitments, structural changes alone cannot resolve chronic shortfalls.

What lies ahead at 80

UN80 marks the U.N.’s 80th anniversary. The question is whether it will be remembered as an adjustment or a genuine transformation. Annan’s tenure showed how reform could breathe new purpose into the institution. Guterres has placed UN80 before member states in a period defined by rivalry, financial pressure, and overlapping crises. It is not a sweeping vision but an attempt to confront the weight of accumulated mandates and insist that both the U.N. and its members accept responsibility for clearing the ground.

For the U.N., this means streamlining its machinery and modernizing its methods. For member states, it demands sharper recognition that mandates carry obligations as well as symbolism, and that clutter cannot stand in for commitment.

If UN80 is to matter, it will be because the U.N. demonstrates it can adapt from within, and because states accept that clarity is a collective duty. The effort of change in this era of reform is not rhetorical; it is the price of keeping the U.N. as the central point of accountability and diplomacy in an unsettled world.