A more balanced distribution of research capacity would make the global AI ecosystem more resilient, diversify its ideas, and give legitimacy to the governance frameworks that follow.

AI is often described as the defining technology of our time, yet the way its knowledge base is created remains profoundly uneven. While governments spend efforts debating strategies of technical development and implementation, the foundations of AI are being laid in research collaborations that are dominated by a few countries, while most others remain observers.

As debates intensify over AI chips, investment flows, data centers and regulation, one question receives far less attention: Who gets to build the knowledge base of AI in the first place?

The United Nations recently approved the creation of an Independent International Scientific Panel on AI and a Global Dialogue on AI Governance. This is a recognition that artificial intelligence is no longer just a technical issue but a governance one. Yet these initiatives risk falling short if they do not confront the deeper imbalance in how AI knowledge is produced and shared.

Why does this matter? Because research is where power begins. Publishing isn’t just about producing papers; it’s about setting the ideas, values, and priorities that determine how AI is built and who it serves. Unequal collaboration today risks embedding those asymmetries into the very fabric of AI’s future.

Recent data on global research collaboration show a familiar story: Scientists and academics in the Global North (the United States and Europe) mostly work with one another, while partnerships that include researchers from the Global South remain scarce. Even as the total volume of AI research grows, North–South and South–South collaborations remain a fraction of total global activity. The result is a two-tiered system: a small group of countries that produce the frontier knowledge collaboratively, and a larger group that relies on it.

If the global AI agenda is written from what could be a narrow set of regional perspectives, so too will be the norms that regulate it.

Polarized hubs

The geography of collaboration also reveals polarized hubs of activity. The United States and Europe continue to be important players in global AI research, but the United States–China axis has been the most dynamic corridor, especially in the fields of computer vision, LLMs, and AI safety. Even amid political tensions, scientific communities in both countries maintain dense networks of co-authorships. Meanwhile, collaborations between China and other regions, or between the United States and partners beyond Europe and China, remain thin. The result is a global research architecture dominated by a handful of bilateral relationships, leaving much of the world at the margins. The collaboration penalty refers to the persistent disadvantage faced by researchers from less-resourced countries when forming international partnerships. In frontier fields like LLMs, computer vision and AI safety, this penalty reflects subtler asymmetries — less about funding, more about governance, compliance and agenda-setting barriers that limit meaningful participation from much of the Global South.

Export controls on advanced chips, unequal access to foundation models and restrictive data-sharing frameworks all reinforce these divides. While Global South institutions have become more active in AI research over the past decade, their contributions often remain peripheral to the spaces where priorities and standards are defined. Yet this imbalance also presents an opening: Frontier fields are still in formation, offering a chance to broaden participation before new monopolies — of knowledge, influence and technological power — become entrenched.

In recent years, analysts have warned that frontier AI capabilities are clustering within a handful of economies, creating a world where most countries risk being confined to peripheral roles, missing not only economic opportunities but also influence over the ethical and institutional frameworks that will govern AI. The trajectory of the past decade shows that this unequal system is not a coincidence but a consequence of how incentives and access have been structured. Unless those structures are deliberately rebalanced, the governance of AI will continue to reflect the priorities of the few, not the collective intelligence of the many.

From debate to action: Four ways forward

The U.N.’s new mechanisms for AI governance are vital steps toward a fairer digital future. But inclusion requires more than a seat at the table. It requires the redesign of how knowledge itself is produced, shared and valued. Here’s how the next phase of these efforts could deepen that transformation.

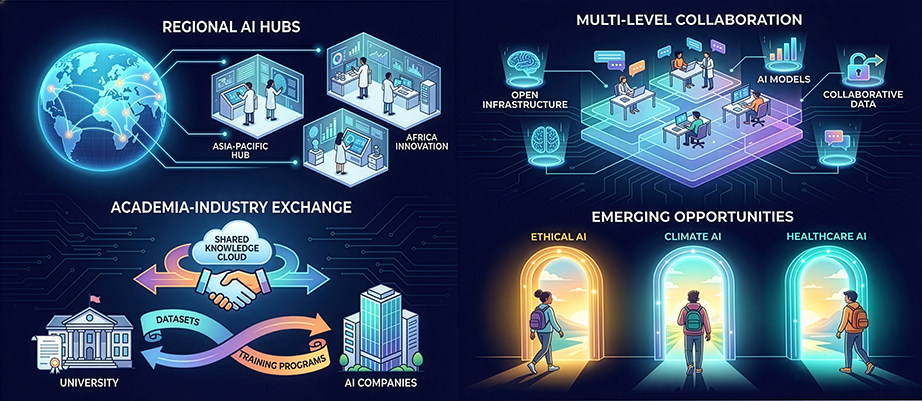

Regional knowledge nodes: Autonomy and connectivity

Beyond promoting inclusion, the U.N.can empower regional AI hubs with genuine research autonomy and formal channels to feed evidence back into global governance. These knowledge nodes should not only connect scientists across borders but also set regional research agendas, lead peer-reviewed publications and develop locally relevant AI standards that the U.N. Dialogue can amplify. Each hub could contribute annual “hub-to-dialogue” reports to the Scientific Panel, ensuring a two-way flow between regional expertise and global policymaking.

Make industrial policy conditional on “knowledge reciprocity”

The Global Dialogue can go beyond general calls for fairness by encouraging member states to embed knowledge-sharing obligations into industrial policy. Foreign AI firms operating in developing countries could co-fund public datasets, co-owned intellectual property and training programs with local universities. To measure progress, these partnerships could be evaluated through transparent metrics: the share of local researchers in leadership roles, co-authored publications and the proportion of local data used in training models. Each country’s knowledge reciprocity plan could be submitted to the Dialogue for peer review, making collaboration a structural feature of AI investment.

Embed structural collaboration mechanisms into the new U.N. bodies.

The U.N. Dialogue already promises inclusivity, but cooperation cannot depend on goodwill alone. It should be hard-wired into institutional design. One option is a Global Research Fund on AI Collaboration, co-financed by member states and regional partners, supporting projects led jointly by institutions from different development levels. The Scientific Panel could also publish an annual Collaboration Equity Index tracking trends in North–South and South–South research networks, data-sharing and access to computing resources. Complementing these, the U.N. could steward a shared Digital Infrastructure Commons — an open platform for datasets, models and compute time accessible to all regions under agreed guidelines.

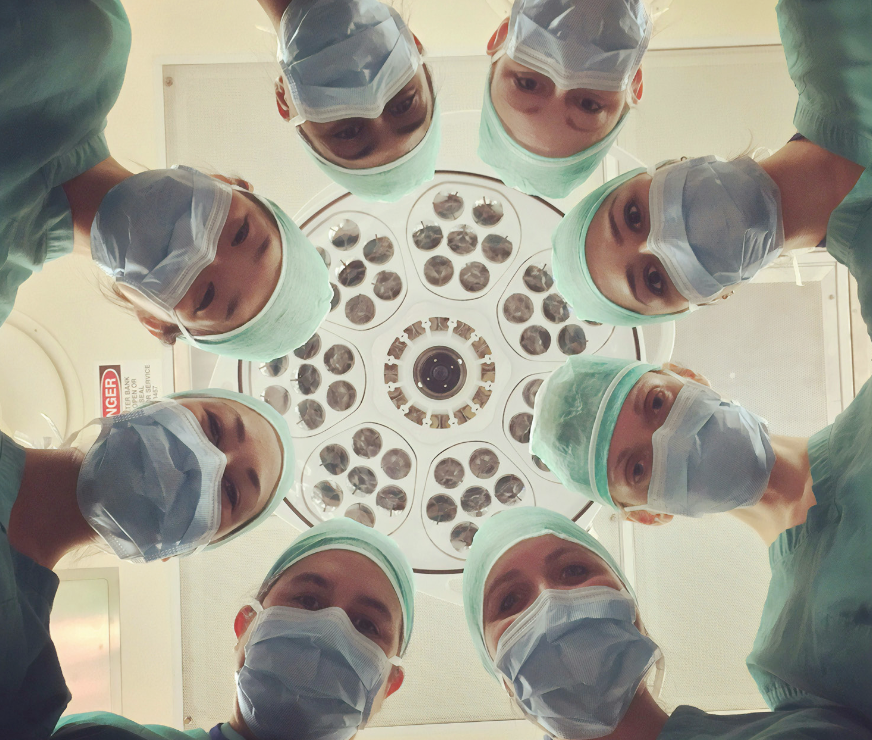

Use frontier fields as “inclusion windows”

The AI landscape is evolving fast, and emerging subfields such as LLMs, AI safety, and AI for climate action offer entry points before new monopolies take hold. The Global Dialogue could launch an annual Frontier Inclusion Challenge, selecting one subfield each year where underrepresented regions receive fast-track grants, compute access, and mentorship from global experts. Progress would be assessed through measurable outcomes: increased publications, new cross-regional patents and diverse participation in standard-setting bodies. The Scientific Panel could spotlight these outcomes in its yearly report, creating accountability and visibility for inclusion at the technological frontier.

The U.N.’s new panel and dialogue have a historic chance to move from principles to practice, from dialogue to design.

A more balanced distribution of research capacity would make the global AI ecosystem more resilient, diversify its ideas and give legitimacy to the governance frameworks that follow. Concentrated knowledge, by contrast, leaves the world dependent on a narrow set of institutions and values.

Artificial intelligence will define the next decades of human progress. Whether it deepens divides or strengthens collective capabilities depends on one simple choice: Do we build it as a closed system or as a shared global endeavor? The answer will determine not just who leads in AI but who belongs in the future it creates.

The views expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the organizations with which they are affiliated.

This article was co-authored by Antonio Reyes-González, research analyst at UNDP; Richard Steinert, international development specialist; and José M. Tavares, professor of economics at Universidade Nova de Lisboa.