The scars of the Dam run deep through the Xingu, where rivers have dried, communities have fractured, and Indigenous leaders warn that the Amazon’s future is slipping away.

On a muggy August night, it rained on the Xingu River, in the heart of the Amazon. As the water poured down on the forest, the jungle sounded like a symphony. Animals celebrated and rejoiced, as if in a show of revenge and resistance. But the Indigenous people of the region are concerned. On the eve of the UN Climate Change Conference (COP30), the population of the state that will host the global event, Pará, warns that they are being abandoned by both the international community and the Brazilian authorities.

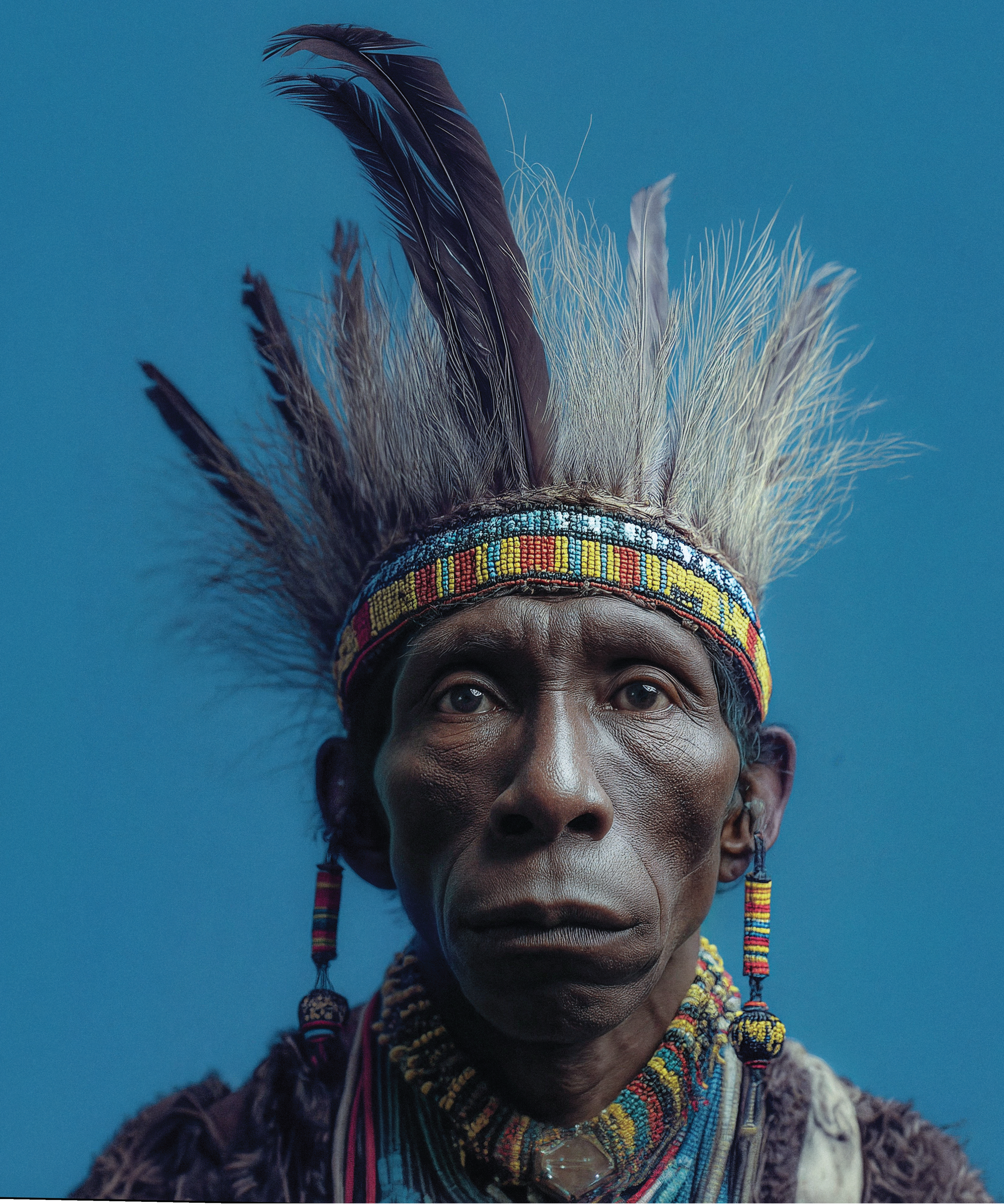

Envoy was in the Altamira region of Pará and witnessed the Indigenous people’s distrust of the world’s environmental direction. Josiel Pereira Juruna, one of the leaders of the Muratu village in the Paquiçamba Indigenous land of the Juruna people, fears that his community will be even further removed from the decision-making process in the coming years. He lives at the epicenter of the damage caused by the Belo Monte Dam, in Volta Grande do Xingu, the fourth largest in the world. But he fears that, with a legislature dominated by the interests of agribusiness and mining companies, his future is threatened by new laws that will facilitate the implementation of new infrastructure projects, such as dams, power plants, cattle ranching, and mining.

“Leaders don’t understand that by harming a river, they are also harming themselves. They think they won’t feel the impact. But one day it will come. Today, we are the ones being affected. But we have somewhere to flee to. They don’t. One day, they will have to pay the price,” warned the Indigenous leader.

For him, even COP30 does not seem to be an answer. His assessment is that world leaders know what needs to be done, and there is no need for the event to come to the city of Belém. “What is lacking is political will,” he said.

Josiel’s pessimism is justified: his life has been completely changed by the impacts of a project that is now a decade old — the Belo Monte hydroelectric plant. The inauguration took place in 2016, and in 2019, the 18th turbine began operating.

The company insists that it produces 6% of Brazil’s energy. What was built on the Xingu River was one of the largest power plants in the world, with 11,200 megawatts of installed capacity.

But the project has become a scar. It altered the natural course of the Xingu River, flooded some areas, dried up others, displaced people who lived on its banks, and caused the death of local flora and fauna species.

Josiel showed the log that marked how far the Xingu River reached before the construction of Belo Monte. According to him, the plant not only diverted the river. It dried up lives and cultures.

Indigenous peoples have witnessed an intensification of illegal logging in their territories and changes in their rivers, and they complain about the lack of assistance from Norte Energia, the concessionaire that manages Belo Monte, and from the government, which promised dialogue but, according to them, has failed to deliver. “The impacts are devastating, especially from the cultural and territorial point of view of Indigenous peoples,” said Lili Chipaia, educator and head of the Indigenous school education division in the municipality of Altamira. “Belo Monte means the violation of rights and ethnic and cultural disruption,” she pointed out.

One of the impacts has been the division of villages and Indigenous groups, with families leaving one place to form a new village. While for centuries ethnic groups divided for reasons of overpopulation or to ensure the protection of their territory, today the situation is different. “The division (of the villages) is the result of the welfare offered by Belo Monte, which is a strategy to weaken each ethnic group,” she warned. According to her, this has a profound impact on the social fabric.

One of the main examples of this new reality is the Trincheira/Bacajá Indigenous Land. Before Belo Monte, there were three villages of the Xikrin people. Today, there are about 50.

Findings of disruption are also part of official reports by Ibama, the federal agency in charge of environmental protection. In one of them, from 2023, the agency states that “the local way of life, which includes fishing and navigation activities, has been harmed by changes in the water cycle of the Xingu River, with flows operated by the Belo Monte Power Plant project.”

At the center of the debate is the war for water. For social movements, the dispute is over the construction of a hydrograph that would save the piracemas and, therefore, life in the Xingu River and especially in the igapó region.

Although the original 1975 project was much larger than the current one, the damming of the Xingu River has interrupted its natural flow, with profound social and environmental impacts. Between 2012 and 2013 alone, more than 1,000 tons of explosives were used for the construction.

As a way to compensate for the impact it would have, the company leading the project created more than 100 mitigation projects. But for riverine communities, Indigenous peoples, fishermen, and the population of cities in the region, nothing will be the same as before.

For environmentalists, despite the projects, the scar on the Xingu has transformed the region into a scenario that the rest of the Amazon fears it will one day experience: the drying up of rivers, the death of dozens of species, and social and environmental changes that many consider irreversible.

In the village of Muratu, Josiel soon realized that there would no longer be enough fish to ensure the survival of his community. As part of the mitigation program run by the company that manages Belo Monte, he began planting cocoa.

The Indigenous man proudly showed reporters his new economic activity. He buys seedlings for six reais and sells a kilo of cocoa for 40. But he was surprised by something unexpected: the invasion of monkeys that steal and eat the cocoa he had planted. Josiel had no choice: he was forced to put up an electric fence to protect his production in the middle of the forest.

For the Indigenous leader, there is a need for the community to once again take on a central role in the destiny of its members in the face of these changes. One way to do this is by producing evidence of the environmental impact of the construction work on the Xingu River.

He is, in fact, one of the protagonists of the Independent Territorial Environmental Monitoring, a network created between Indigenous people, fishermen, and scientists to propose a water regime that allows the continuity of the piracemas and prevents ecocide.

“We noticed that the impacts did not appear in the official reports, so we started our independent monitoring,” he explained. The first survey was on food. The study found that, before the plant, 80% of the Indigenous people’s food came from the river. Afterwards, 70% came from the city.

After that, the group began monitoring fish and their reproduction. “We would travel along the river at night and see that certain fish were no longer there. Something was wrong,” he said.

Today, he says that the network’s studies have already shown a decline in fish reproduction, that the igarapés are being affected, that fruits are ripening out of season, and that fish are unable to feed at the right time. “We have shown that some species of fish that we consume no longer exist. We have been able to show that there are fish with malformations,” explained the Indigenous leader.

As if that were not enough, navigation on the Xingu River has been disrupted. “We have lost certain fishing spots. There has also been a cultural loss. Certain things we learned today no longer exist. We can no longer teach them, because that environment no longer exists,” he added.

What Josiel discovered is also confirmed by fisherman Raimundo Braga Gomes. “The river was my father and my mother. Today, everything is gone,” he said, taking the reporter aboard a speedboat to the cemetery of trees flooded by the Xingu.

Mr. Raimundo and hundreds of other residents of the Volta Grande do Xingu region were ordered to leave their homes to make way for the Belo Monte construction project. A fisherman in the region between 1977 and 2012, he says, it wasn’t just the fish that disappeared. His life, as he knew it, disappeared.

That act was not just an administrative measure. It instilled fear in the population and promoted the erasure of entire communities. Compensation was established. But Raimundo sees no point in any of that. “What good is compensation? The river is gone forever. It was the death of our lives,” he lamented.

Alongside the reporter, Raimundo visited what is now known as the forest cemetery, or paliteiros, by boat. An area flooded by the dam that ended up becoming a place of death. “Not even birds fly over the river anymore. What are they going to eat?”

The desolate image of Raimundo reflected in the silvery waters of the Xingu River at the end of the day was just a mirror of the reality of an entire community.

In Xingu, there is no shortage of victims. To relocate thousands of people who were expelled from their homes, Norte Energia created new neighborhoods on the outskirts of Altamira. Artificial neighborhoods whose streets led nowhere, and with poor transportation.

In total, 22,000 people were placed in 6,000 houses. They were all the same, measuring 63 square meters. They were all insufficient for families that did not meet city standards. Families that, months after receiving compensation, went bankrupt.

The urgency of the move and an uncertain future further increased the anguish of many. Urban resettlement dismantled the social fabric, and communities were broken up. Neighborhoods were destroyed and, even in crime, factions were mixed.

The result was not long in coming. The homicide rate increased by 1,100% between 2000 and 2015.

The plant completely changed the lives of thousands of people. At the height of construction in 2013, between 20,000 and 40,000 new residents arrived in Altamira, which did not have the infrastructure to accommodate those workers.

The impact was felt in real estate prices, in the explosion of crime, and even in the city’s brothels. During those years, the women who worked in these places went on strike. They could no longer serve the hordes of men who knocked on their doors on weekends.

In an attempt to dialogue with Norte Energia, they asked that the salaries of the plant’s employees — the dam workers — be paid alternately during the month, so that there would not be a rush to the city’s brothels on the same weekend. The company, however, refused to make salary payments more flexible.

Ten years later, the reporter passed by the shed that served as a brothel, near the Transamazônica, the controversial highway. Today, it is empty. At its gate, there is only a “for sale” sign.

If the plant casts a shadow over the Xingu River, the fear of entities, Indigenous peoples, and experts is that an acceleration in the approval of new projects will set a new pace for the disruption of an entire Amazonian civilization.