We are definitely not on track to reach the climate targets of the Paris Agreement. In about two years, humanity will have used up the remaining carbon budget – that is, the emissions that can still be released to the atmosphere – consistent with the goal of keeping global warming to below 1.5°C. Yet, despite these sobering prospects, some important progress has been achieved in recent years on several fronts.

Rather than despair, we should take a closer look at positive developments and understand how these can help accelerate the transition to climate neutrality. If technological, political, and social progress reinforce each other, the transition to climate neutrality can soon pick up considerable momentum.

Technological progress

Perhaps the most encouraging technological development is the rapid progress in clean energy technologies. Over the last decade, the costs of solar power have dropped by about 80% and offshore wind power by more than 70%. This makes renewables competitive with fossil fuels even without dedicated climate policies. For instance, Kenya now produces about 94% of its electricity from renewable sources, most importantly geothermal energy.

Costs of batteries have also declined sharply, by about 80% in the last ten years, putting their widespread use to stabilize power grids within reach. Cheaper and better batteries have also turned electric vehicles into a superior alternative to the internal combustion engine in terms of performance and costs.

Heat pumps are increasingly used in buildings, reducing demand for oil and natural gas. The advantages in terms of energy efficiency and the possibility to run them with electricity from renewable sources make heat pumps attractive for decarbonizing the residential sector. The fact that Sweden, Finland, and Norway display the largest share of heat pumps worldwide shows that this technology works well even in cold climates.

Heat pumps are also a cornerstone for electrifying industrial production, such as food or pulp and paper. For example, more than 90% of industries in the EU could switch from fossil fuels to electricity by 2030. Moreover, novel approaches are being developed that promise decarbonization of the remaining ‘hard-to-abate sectors’, such as steel and cement, at modest costs.

Social progress

Climate awareness is growing everywhere across the globe. In a recent poll, Indonesia and Saudi-Arabia emerged as the countries with the lowest concern about climate change, but even there, the majority of the population were ‘concerned’ or ‘very concerned’ about global warming. As a consequence, people are changing their consumption patterns, investment behaviors, and investment decisions to some extent. Registrations of electric vehicles have grown from roughly 3 million in 2020 to more than 14 million in 2023, while new registrations of conventional vehicles with combustion engines are in steady decline. In China, the largest market for cars, electric vehicles already constitute the majority of newly sold vehicles. At the same time, in many industrialized countries, fewer people entering driving age get driving licenses.

Investments are gradually shifting from brown to green. The market capitalization of firms producing clean energy technologies is estimated at about USD 4 trillion. Cleantech start-ups attract almost USD 100 billion in venture capital annually. More than 1,600 institutional investors, such as pension funds, accounting for a combined value of more than USD 40 trillion, are divesting from fossil fuels.

Citizens are increasingly taking legal action against firms and governments to hold them accountable for doing too little to reduce emissions. Per year, there are about 200 such climate cases. For instance, in 2024, the European Court of Human Rights found that the Swiss government violated human rights by insufficiently protecting senior citizens against health risks related to climate change.

People are also protesting for measures to curb climate change. Since March 2022, almost 120 climate protests have taken place across the globe, and more than one million people participated in the Global Climate Strike in September 2023.

Political progress

In many countries, policymakers have paid heed to citizens’ demands for climate action. Decreasing economic costs ease political resistance against climate measures, and transitioning to clean energy is increasingly seen as an opportunity for economic modernization and job creation. Reducing dependence on fossil fuel imports provides a further motivation for shifting to alternative energy sources.

There are now more than 5,000 climate laws in place worldwide. The stringency of implemented climate measures has increased considerably over time, in particular in low- and medium-income countries. More than 150 countries and many sub-national actors, such as cities or companies, have adopted net-zero targets.

Phase-out mandates provide a clear commitment to guide investment decisions. Such mandates exist for coal-fired power generation, fossil heating, and vehicles. Norway, for example, has a range of incentives in place that make it unattractive to still register vehicles with internal combustion engines, and in 2024, about 90% of newly registered cars were electric. Ethiopia has already banned imports of cars with internal combustion engines.

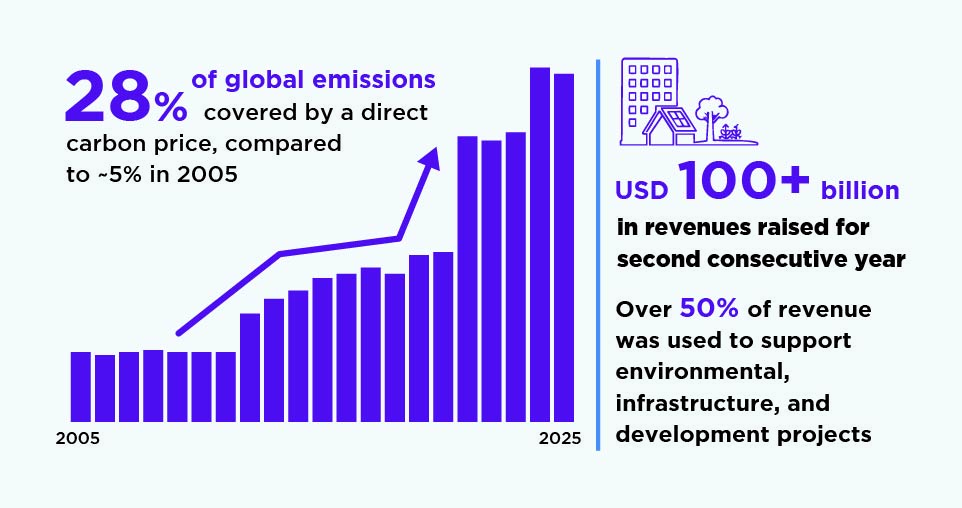

More than 70 jurisdictions use carbon pricing, a central element of effective strategies to reduce emissions. The EU was the first jurisdiction to extend carbon pricing to imports, thus incentivising foreign firms to reduce emissions, and the UK, Norway, and Canada have announced similar schemes.

How it could all come together

Technological, social, and political drivers of climate policy are closely intertwined. Technological progress makes it easier for people to switch to climate-friendly alternatives and for decision makers to implement climate measures, and well-designed climate policies can drive further technological progress and facilitate behavioral change. If things go well, we can end up in a virtuous circle in which progress in one area sparks progress in others, thus dramatically accelerating the transition.

There has been some backlash against climate policy, most notably the backtracking of the Trump administration on earlier U.S. commitments. But also in the EU, the willingness to pay for emission reductions is waning in view of a slowing economy and increased defence spending. These developments are regrettable, but they are unlikely to stop the market forces driving the transition to clean energy. While the US is pulling out of climate action, other countries, in particular China, are filling the gap and stepping up their ambition to take on a leading role in international climate diplomacy.

It is far from certain that the transition to climate neutrality will succeed. But it is not impossible, and decisive action to prevent the most serious consequences of climate change is still in our hands.

Dr. Michael Jakob is an independent researcher and consultant operating under the label Climate Transition Economics. He is the author of The Case Against Climate Doom: An Economist’s Guide to Climate Optimism.

The opinions expressed in op-eds are those of the contributors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the magazine.